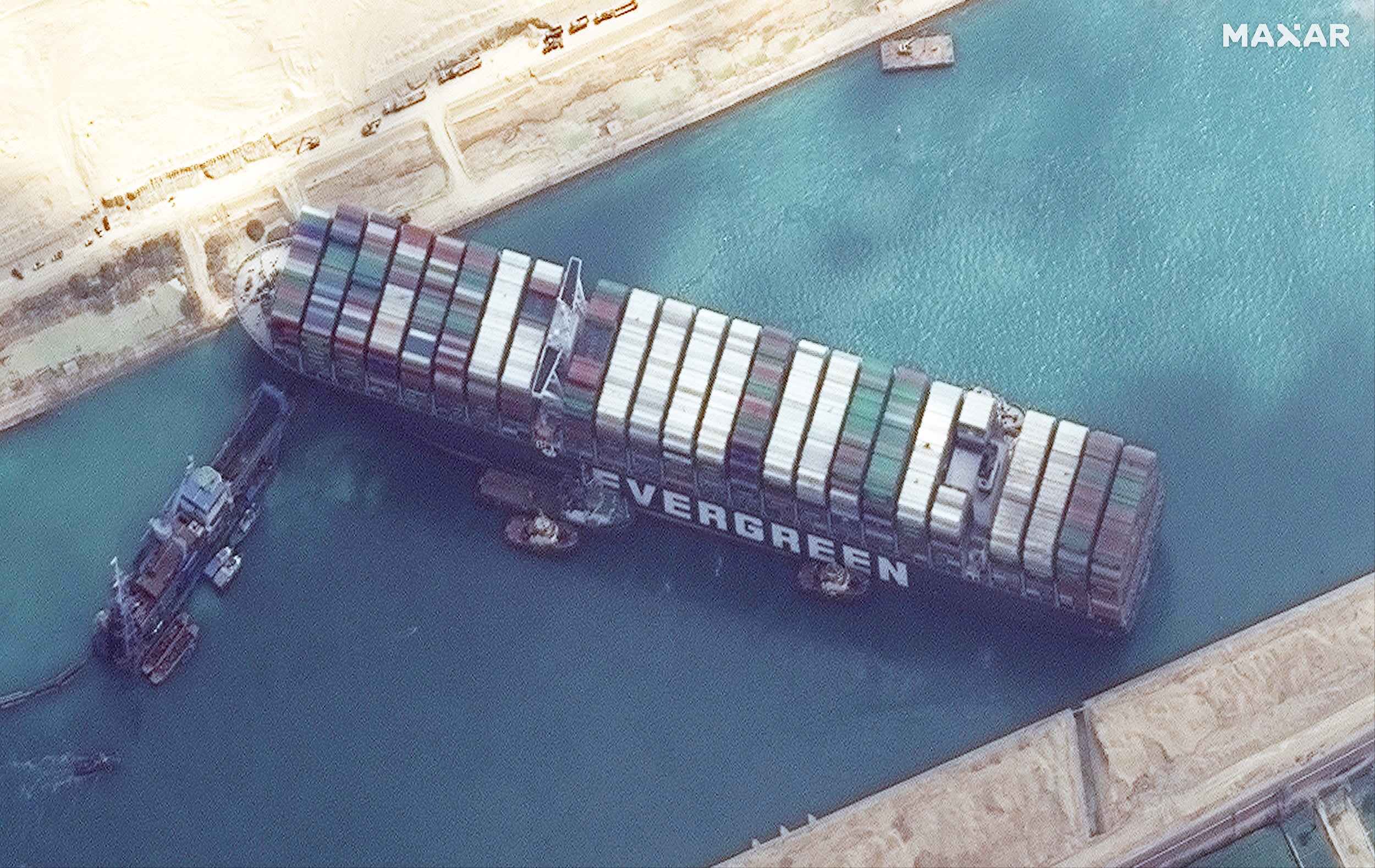

On the morning of 23 March, the Suez Canal was blocked for 6 days after the accidental grounding of Ever Given, one of the largest container ships in the world. What the 400-metre-long vessel (longer than the width of the Canal!) unfortunately did was that it ended up wedging itself diagonally across the waterway at such a location that not a single vessel could pass northbound or southbound.

The ship was finally floated on 29 March afternoon and moved, under tow, to the Great Bitter Lake—the Canal’s midway point and also its widest area—for technical inspections, inquiry, repairs….whatever. The Suez Canal Authority (SCA) allowed shipping to resume that evening. At the time of writing, the Ever Given is still there at anchor.

The Suez Canal is one of the world's busiest trade routes, and this obstruction had a significant impact on world trade, estimated at about USD 10 billion. While governments, ship-owners, cargo owners, ship managers, SCA, charterers, insurers, etc. go to town over the next few months suing each other for damage or losses incurred, an official report is awaited. As with most official reports, this one too may obfuscate facts, muddy the waters, protect those it wants to…. so I’m not exactly holding my breath waiting for it.

Several friends have asked me what I think went wrong with the ship on that fateful day. Having been up and down the Suez Canal dozens of times in my 30 plus years as a merchant ship captain, I think I’m qualified to hazard a guess. Well, here goes….

Two SCA licensed marine pilots along with their crew must have boarded that morning as the northbound Ever Given approached the Newport Rock Channel, the southern end of the Canal. (The government of Egypt requires ships traversing the Canal to be boarded by an Egyptian ‘Suez crew’, including one or more official maritime pilots from Egypt's SCA who will command the ship and take over from the regular crew and the captain. That is the port regulation.)

The notoriety of the Egyptian Pilots in the Suez Canal is as old as the Pyramids themselves. (Well, almost.) Ask any seafarer why the Suez Canal is called Marlboro Country. He/she will enlighten you.

As is their wont, these pilots must have demanded their ‘baksheesh’ in the form of cigarette cartons, coffee jars, etc. as their divine right within minutes of boarding, before settling down to take charge of the navigation. A transit of the Suez Canal is always a harrowing experience for Masters of ships, as they are forced to deal with corrupt officials who hound them relentlessly. Several reputed Companies have forbidden gratifications, and the poor Master’s hands are tied. As a result, several pilots raise tantrums and threaten to cause an accident when Masters of ships are unable to meet their persistent demands. And some do! SCA has done nothing to discipline these pilots.

Depending on the resistance of the Ever Given’s hapless captain or his negotiating skills, the mood and tone of the navigation team must have been set as the gigantic ship made its way up the narrow channel.

En route, the ship was caught in a sandstorm. (Surely the pilots would have been aware of the day’s weather forecast?) The strong winds, which reached 40 knots (74 km/h), caused the hundreds of box-like containers atop the deck area—tightly secured to each other to form a large, solid block—to act like a sail. Thus the ship was pushed easily away from its track in the narrow channel. The momentum of a heavy ship blown off course must have been difficult to counteract. The ship drifted to the left bank, according to the satellite imagery of the incident circulating on social media. At the left bank, hydrodynamics in shallow waters came into play. The Bank Effect caused the bow (forward-most part) of the ship to be pushed away from the bank and its stern (rear end) to be sucked in towards it. Experienced mariners are aware of this phenomenon and take appropriate action with counter helm and adjustment of speed. But the sideways push of the strong wind too was at play here, and the ship’s movement could not be controlled. It ran aground on the right bank, resting firmly across the channel.

There were other factors too which need to be answered. The ship was steaming at a speed of 13 knots—obviously ordered by the pilot—a speed too high for a channel like that. Personally, I have never ever transited the Canal at a speed more than 7 to 8 knots. At that speed, the reaction time to act in an emergency would reduce drastically, wouldn’t it? Like the reaction time difference to avoid a car accident at 80 km/h and at 40 km/h? Okay, I am guessing that the speed was possibly ordered to counter the drift due to the wind, but it rendered the bow thruster (an auxiliary propulsion device at the bow of a ship to aid in manoeuvring) ineffective, when it was needed the most.

The issue of crew fatigue too cannot be ruled out. To make the Canal transit, the captain and his crew must have been up at 4 am that morning to get the ship ready, weigh anchor and proceed to the pilot station to reach at the appointed time. Fatigue definitely affects one’s ability to handle an emergency, when so many things go wrong at the same time.

So what I’m saying is that the pilot made errors of judgment in handling that ship. I’m not saying that he did it deliberately. To err is human after all. But there lies the rub—as per maritime law, pilots are never held responsible for any navigational incident. It is always the ship’s master, even when the pilot screws up. So I don’t have to wait for the judge and jury’s verdict to know who will be squarely blamed for the incident. It will be the ship’s captain, of course, for not reacting in time to save the situation. The buck stops there. It’s in his job profile. Mr. Fall Guy.

There aren’t that many jobs with this amount of responsibility on a single person. Try to think of any other job where one or more mistakes by a single person other than yourself has the potential to bring the entire world's supply chain to a grinding halt, and puts the incident on every news channel and WhatsApp group for an entire week or more.

Playing a game on the CNN website or reading a few articles about momentum, bank suction, and effects of wind on steering a large ship do not qualify us to judge a Master Mariner. This is why I will not be judging the captain of the Ever Given.

Neither should you.

Beetashok Chatterjee is the author of ‘Driftwood’, a collection of stories about Life at Sea and ‘The People Tree’, another collection of stories about ordinary people with extraordinary experiences. A retired merchant ship’s captain by profession, he lives in New Delhi with his memories of living more than 40 years on the waves.

His book is available on Amazon. Click here.

Comments