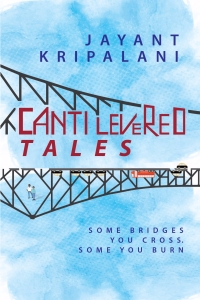

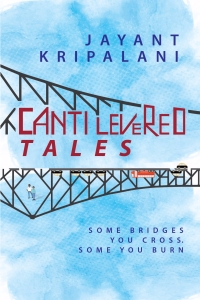

Cantilevered tales is a story about people, their quirks and why they become who they become. And lots of laughter! In the author's own words, 'This is about a group of inept people who you want to reach out and protect but you discover are more than capable of taking care of not just themselves, but of you too.'

Given here is the first chapter from the book.

1

The Bridge

‘Is this Haora Bridge or Laora Bridge?’ asked Ashutosh Babu, my colleague with whom I shared a room at the Writers’ Building.

I wasn’t shocked at all. This is a question he had asked every day for the last ten years as we sat in a bus on our way back home.

Bally Bridge was the alternative way across the river but it was not on our route. It was somewhere over there, a few miles upriver where things really didn’t matter.

This was the real bridge, the absolute connector of west to east. Thousands of cars, buses, lorries, thela garries, rickshaws and even trams and of course a hundred thousand or so pedestrians traversed the length of it, both ways, everyday.

And on my way home, six days a week around six in the evening, I’d be sitting in a State bus, in a window seat, in the middle of a traffic jam, in the middle of this bridge—the Howrah Bridge.

Ashutosh Babu, who was about a generation older and as cranky as an MLA who had to follow a party Whip against everything he stood for, sat next to me in the bus. He sat near me in the office at Writers’ too; so the only respite I got from his company was when I got off at my stop and for the rest of the night afterwards. I’m not complaining. He never said much and never intruded in my space.

So there we were.

It was just another day.

It was 6.15 in the evening.

Like every other day, I would have nodded at his comment and looked out of the window at the impossible jam we were in.

I was, however, a bit tense that day, having spent a harrowing hour or so with a Minister who wanted to dispense undue favours to a crooked builder—a major contributor to his election fund. This was a Minister with whom I had little or nothing to do with at the best of times. In fact even builders and I had avoided each other quite successfully. This particular builder was the Minister’s current favourite and smelled like an overripe and rotten jackfruit. Was that the smell of corruption? Understandably, my mood that evening was far from normal. Had it been your normal dreary day, I would have let Ashutosh Babu’s statement pass as I had done for the past ten years. But not that day.

‘The fact that it hasn’t collapsed is a tribute to British bridge building, don’t you think?’ I blurted out.

He was as taken aback as I was, by my question.

After ten years, he was being provided with a response to a question which one had to agree, was purely a rhetorical one.

And my tone did border on the rude.

Before I could apologise, he moved about two inches away from me on the hard bench-like planks that pretended to be seats. I could see that he was in a state of shock. He was not used to being replied to. But I didn’t let up.

‘Many bridges have been built since Independence.

Those, Ashutosh Babu, are indeed laora bridges,’ I went on, knowing I should have kept quiet.

‘They have had grand openings, have been named after old Indian heroes and freedom fighters and have had eulogies written about the brilliant engineering that has produced them. And some have collapsed, some have tilted over, and the surfaces of some of them look like they’ve been attacked by small pox,’ I added before I could stop myself.

Ashutosh Babu, who at the best of times was the mildest and most taciturn of men I had ever met, had no idea how to handle my uncalled for response and arguably, very rude behaviour.

He moved four more inches away from me on the two-seater that we shared. And retreated into an uncomfortable silence (and an uncomfortable position; half his bottom was hanging off the seat) as I ploughed on with my story of the bridge.

‘Ashutosh Babu, this bridge is the only link we personally have to Calcutta. There are two other bridges but both are so far upriver that they don’t matter to us. There is one being constructed downriver but so much water has flown under that plan. . . well!’

He glanced at me from the corner of his eyes. Suspiciously.

“How dare I break the ‘rule’ after ten years?” he seemed to be asking. He was just expressing himself as he did every day. Why was I behaving in this unexpected and uncalled for fashion?

‘Believe it or not, this venerable old bridge was originally a pontoon bridge,’ I ploughed on.

I didn’t seem to have any control over my tongue or my thoughts.

“Tai naki?” his look seemed to say, as he inched further away.

A crowded aisle, crammed with passengers, was the only reason he was still sitting where he was. I could see he was itching to join them, make his way through them and get off the bus if he could. ‘It was constructed piece-by-piece in England,’ I went on relentlessly, ‘shipped to Calcutta, assembled here, and while it was being laid across the river, or maybe when it was due for commissioning, the details are a bit hazy, a cyclonic storm struck.’ Ashutosh Babu looked at me, hoping perhaps that I would shut up or crawl back into whichever hole I had crawled out of, or drop dead, whichever came first.

Undeterred, I went on.

‘A large steamer called the Egeria—named after a Brazilian water plant or a water nymph, no one was quite sure—was ripped from its moorings, carried along the river on a collision course, to the bridge. Three pontoons sunk. Two hundred feet of the bridge damaged beyond repair.’

The sound of a lonely foghorn floated up the river to us. We both looked out of the window but could see nothing in the evening haze.

‘Many decades later, a journal discovered in Russell Exchange, an old auction house in Calcutta, written in all likelihood by a First Officer of the Egeria, talked more of the name of the steamer than the storm that destroyed it,’ I continued with my story.

The aisle of the bus was now crowded with even more passengers and until we reached the last stop, there was nowhere Ashutosh Babu could escape to.

‘Ashutosh Babu, I am paraphrasing a bit but what the First Officer wrote were words to the effect of—“It is indeed a sobering thought that the steamer was christened Egeria. Egeria was a ‘goddess’ that cohabited with Numus Pompilus, the second legendary king of Rome.”’

Two teenagers sitting behind us giggled. I presume they giggled at the use of the word cohabit.

Ashutosh Babu turned around and glared at them. Ministers of State had quailed at that glare. These children didn’t stand a chance. They shuddered into silence.

‘Numus Pompilus was the second legendary king of Rome, after Romulus,’ I went on relentlessly. He looked longingly at the aisle hoping for an inch of space that would accommodate him and allow him a chance to run.

‘Indeed history records, and I quote, that, “Egeria dispensed wisdom and prophecy in return for libations of water or milk.” An accident of the kind that occurred, the diary went on to say, could only be because adequate libations had not been offered to her memory and the only libation that was prevalent on board was a very evil-looking and equally evil tasting black rum.’

I could have written a White Paper describing the disbelief on Ashutosh Babu’s face. ‘Whether this was written in all seriousness or in jest, no one will know,’ I said.

‘“As I waited here on the banks of this river to hell, for a ship in need of a First Officer, I saw the completion of the pontoon bridge. It was one thousand five hundred and twenty-eight feet long, sixty-two feet wide. It had seven-feet-wide pavements on either side, or so the British engineers working on the bridge, with whom I had entered into a friendship, out of sheer loneliness, told me.”

About five years after the bridge had been commissioned, the dynamo at the Mullick Ghat Pumping Station supplied electricity to the street lamps on the bridge.

The same First Officer of the good ship Egeria, now visiting in another steamer, reported in his journal that the, “dim, flickering lights were a pleasing surprise and brighter than the hand-lit lamps that had hitherto been in use, and could be relied upon to throw a steadier light on the comings and goings of the bridge.”’

Ashutosh Babu looked more than suspicious. His raised right eyebrow, questioning silently and apprehensively the authenticity of my information. ‘I have his journal at home if you want to check the veracity of my statement.’

Embarrassed at having hinted that the antecedents of my story might have been suspect, he moved back, closer to me, by a couple of inches.

I have not come across any descriptions of the pontoon bridge opening up at night for the passage of vessels. All kinds of vessels went through except ocean steamers, which went across only during daylight hours, but it must have been a magical sight at night—the bridge parting, foghorns heard wafting over the water, the vessels sailing through. However, like all good ideas, the pontoon bridge outlived its usefulness. Daily traffic across it multiplied exponentially and by 1905, the Port Commissioners began planning for a new improved one.

This Howrah Bridge. And this Howrah Bridge was anything but a laora bridge.

But I knew what Ashutosh Babu meant. He wasn’t talking about the bridge at all. He was talking about the life he and all of us stuck on that bridge had chosen to lead.

About the Author

Comments